FREE: EIGHTY NATIONS BURNING: The Undeclared War Against 380 Million Christians Now Documented

One in seven Christians worldwide faces systematic persecution. The violence is not random.

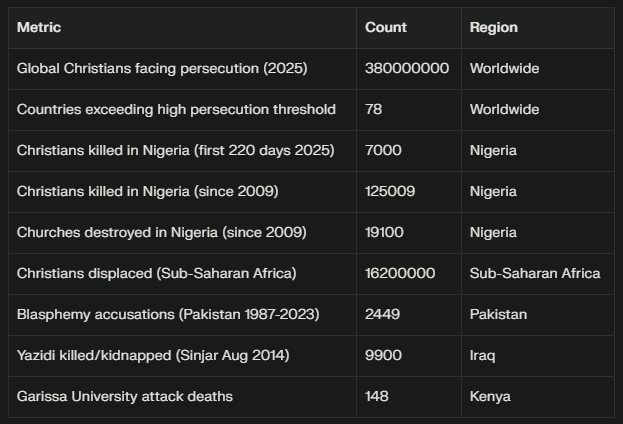

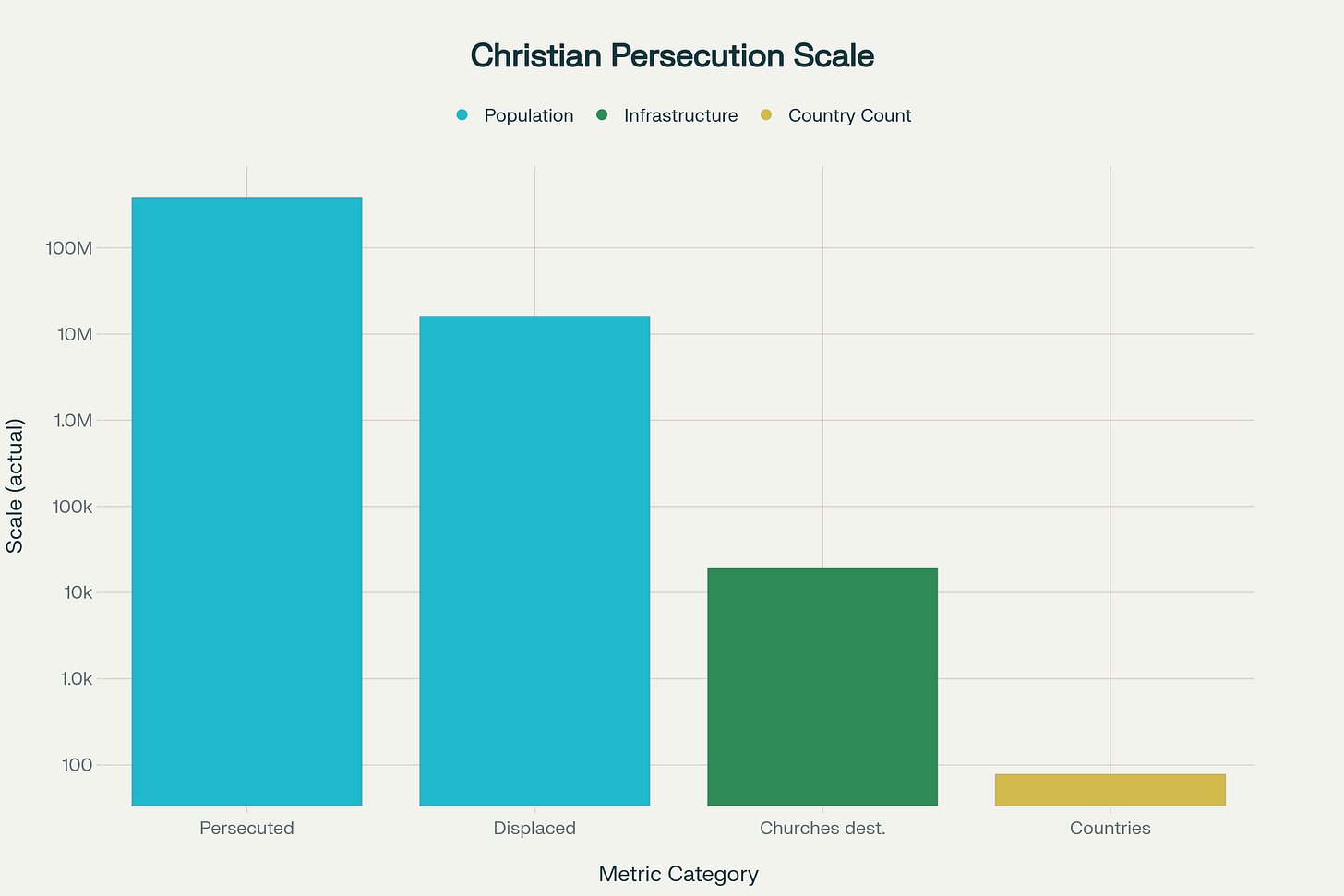

The numbers appeared in parliamentary briefings and NGO reports throughout 2025, but they landed like an indictment. Across 78 countries, Christians now meet the threshold for “high, very high, or extreme persecution.” In 78 nations, not 50. Not a dozen. Seventy-eight.

This represents a shift in global religious violence that demands forensic examination. Over 380 million Christians are living under conditions of active hostility—an increase of 15 million in just one year. The Open Doors World Watch List, certified by the International Institute for Religious Freedom and produced after three decades of rigorous methodology, does not hedge. The scale is no longer exceptional. It is structural.

The violence cascading across sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and the Middle East follows a pattern: jihadist organizations explicitly claiming Islamic justification target Christian populations with demonstrable intent. The killing is not incidental to resource conflicts or political instability. It is theological. It is systematic. And for millions of displaced persons living in camps across Africa, it is ongoing.

What follows is not an opinion on Islam itself—a faith practiced peacefully by nearly two billion people. What follows is a factual reconstruction of how extremist organizations weaponize selected Islamic theology to justify genocide, how they deviate systematically from mainstream Islamic scholarship, and how the international community has failed to contain them.

NIGERIA: 35 CHRISTIANS EXECUTED PER DAY

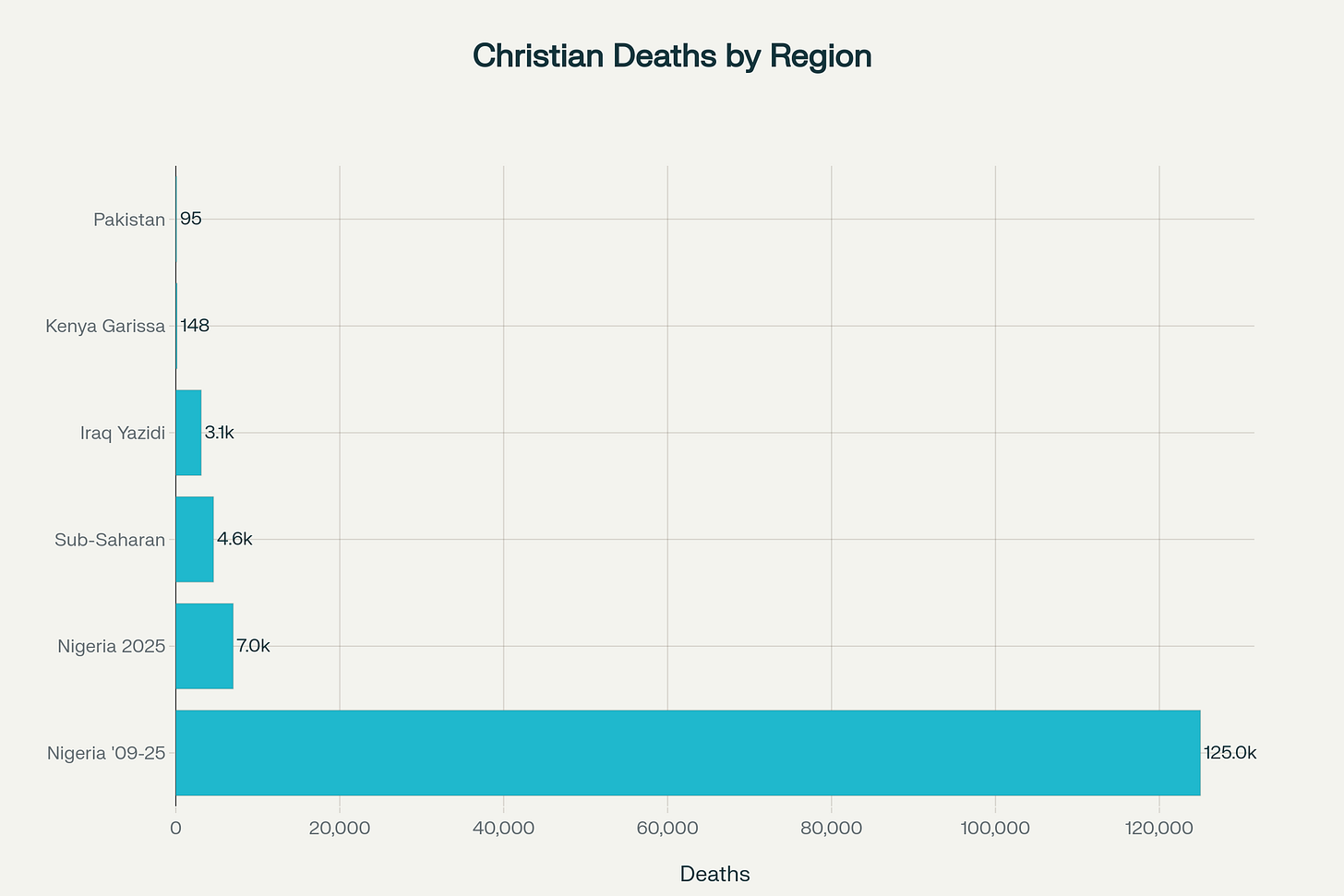

Thirty-five. Every single day. In the first 220 days of 2025, approximately 7,000 Christians were killed across Nigeria, translating to an average of 35 deaths daily according to the International Society for Civil Liberties and Rule of Law. This is not a projection. These are documented killings recorded by on-the-ground human rights monitors.

The figure represents a staggering trajectory. Since Boko Haram launched its insurgency in 2009, documented Christian deaths in Nigeria have reached 125,009, with an additional 60,000 Muslims killed for being deemed “liberal” or insufficiently radical by the jihadist apparatus. In that same sixteen-year window, approximately 19,100 churches have been destroyed, attacked, or permanently shut down—an average of one hundred churches every month, or more than three per day.

The scale is not hyperbole. The International Society for Civil Liberties and Rule of Law, a Catholic-inspired human rights group led by researcher Emeka Umeagbalasi, compiled these figures through exhaustive documentation. “A church does not simply close itself,” Umeagbalasi explained. “It takes violence, intimidation, or bloodshed to empty a parish.” When the organization counted every church that had been destroyed or abandoned due to violence since 2009, it reached 19,100. The arithmetic is inescapable: 19,100 churches over 16 years equals 1,200 per year, 100 per month, three per day.

Beyond the churches lie the bodies and the displacement. More than 600 Christian clerics have been abducted in Nigeria—250 Catholic priests and 350 pastors—with dozens executed. Over 7,900 Christians have been kidnapped for ransom, a strategy designed to destabilize Christian families and deplete church resources. Approximately 20,000 square miles of Christian-held land have been seized. The jihadist groups explicit goal, according to court filings and intercepted communications analyzed by Intersociety: eliminate an estimated 112 million Christians from Nigeria within the next 50 years, mirroring the 19th-century Sokoto Caliphate that dominated northern Nigeria.

Trump’s November 2025 threat of military intervention reignited the debate, but overshadowed the mechanics of the violence itself. The perpetrators are not unified. The killing apparatus comprises at least 22 distinct jihadist organizations operating across Nigeria’s north, northeast, and increasingly into the Christian-majority Middle Belt. The main actors are documented:

Boko Haram and ISWAP (Islamic State West Africa Province). These two organizations, the latter explicitly pledged to ISIS’s global franchise, have built an insurgency centered on establishing an Islamic caliphate across Nigeria’s Sahelian territories. Boko Haram’s founding name itself signals ideology: the organization translates the Hausa word “boko” (deception, fraud) combined with the Arabic “haram” (forbidden). Their slogan: “Western education is forbidden.” Their official name is Jama’atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’awati wal-Jihad—”The Group of the People of the Islamic Law for Propagation of the Prophet’s Teachings and Jihad.” The ideology preceded Boko Haram’s founding in the early 2000s. Northern Nigerian academics, traditional rulers, and clerics had spent decades arguing that Western secular education represented a colonial imposition that undermined Islamic values. Boko Haram weaponized this grievance into an insurgency.

Since 2009, Boko Haram and its splinters have explicitly targeted Christian churches and communities. They have claimed over 40 documented church attacks, executed pastors on camera, massacred congregations on Christmas and Easter, and coordinated kidnappings of schoolgirls to prevent Christian education. The ideological framing is direct: Christians are labeled “kuffar” (unbelievers) or “allies of a corrupt secular state,” making attacks a form of jihad against a hostile camp, not random crime.

Fulani-identified armed groups. The “Fulani herders vs Christian farmers” narrative oversimplifies a more complex pattern of religious violence overlaid on resource conflict. Nomadic Fulani pastoralists, predominantly Muslim, have clashed with settled Christian farming communities over grazing rights and land access in Nigeria’s Middle Belt. Desertification has intensified pressure as the Sahel recedes south, pushing herds into Christian-majority agricultural zones. But the violence cannot be explained by pastoralism alone. Fulani militants—distinct from ordinary herders—have increasingly adopted religious framing, applying jihadist ideology to what are fundamentally territorial disputes. Between 2019 and 2023, Fulani-identified attackers were responsible for 55% of recorded Christian deaths in Nigeria, according to Open Doors research. They operate with tacit support from some local governments and security forces, enabling coordinated massacres in Christian villages, particularly in Benue, Plateau, and Taraba states.

In May 2025, Fulani attackers killed up to 36 Christians in coordinated assaults. In June 2025, the same pattern escalated to 200 deaths in Benue State. Attacks are frequently timed to coincide with Christian holidays or agricultural seasons when farmers are vulnerable. The religious dimension is deliberate: churches have been specifically targeted, Christian women have been subject to sexual violence, and Christian men have been executed after religious identification.

The displacement cascading from this violence is catastrophic. More than 16.2 million Christians across sub-Saharan Africa have been forcibly displaced from their homes, living in Internally Displaced Persons camps in conditions described by Open Doors as “unbearable.” In Nigeria alone, roughly 9 out of every 10 religiously motivated killings in sub-Saharan Africa occur, meaning that as Nigeria burns, the continent burns with it.

Chart showing comparative death tolls across regions and time periods now embedded.

THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO: BEHEADINGS IN CHURCHES

In February 2025, Congolese authorities discovered a mass grave in Kasanga, in North Kivu Province near the border with Uganda. The discovery followed a three-day coordinated abduction. Between February 12 and 15, armed militants had systematically moved through villages in Mayba in the Lumbero territory, detaining approximately 100 Christians and marching them to a Protestant church affiliated with the Evangelical Community in Central Africa. Inside that church, the perpetrators executed their prisoners by beheading. Seventy Christians, including children and the elderly, were found with their heads severed. The remains were discovered by family members and confirmed by Open Doors and the Aid to the Church in Need foundation.

The perpetrator was the Allied Democratic Forces, a Ugandan-origin jihadist organization that in 2019 pledged allegiance to ISIS and adopted the designation ISIS Central Africa Province (IS-CAP). The ADF operates across eastern DRC with backing from elements within the Ugandan diaspora and transnational jihadist networks. It is not a rogue cell. The ADF has orchestrated a systematic campaign against Christian communities, particularly in the Ituri Province and North Kivu, with the explicit aim of establishing Islamic State governance in Central Africa.

Four months after Kasanga, in July 2025, the pattern repeated with greater brutality. On July 26-27, ADF fighters attacked a Catholic church compound in Komanda, Ituri Province, during a nighttime worship gathering. The attackers entered around 1 a.m., targeting a building where congregants were sleeping ahead of Sunday mass. Using machetes, blunt instruments, and gunfire, the militants killed at least 40-45 people according to varying accounts, with Human Rights Watch documenting at least 33 deaths immediately from injuries sustained during the attack. ISIS claimed responsibility via Telegram, as is its organizational protocol, stating that 45 people had been killed.

A survivor recounted: “They told us to sit down, and then started hitting people on the back of the neck. They killed two people I didn’t know, and that’s when I decided to flee with four others. We managed to run away—they shot at us but didn’t hit us.” This is not collateral damage in a broader conflict. This is precision targeting of Christians at worship.

The displacement from DRC violence has created a humanitarian catastrophe. In March 2025, as ADF violence intensified, hundreds of thousands of people fled eastern DRC, with nearly 80,000 crossing into neighboring countries, including 61,000 into Burundi. U.N. peacekeepers stationed in the region have documented the scale of displacement but lack capacity to protect fleeing civilians as the ADF and other militia groups maintain territorial control and commit systematic sexual violence against Christian women. Pastors and Christian leaders are specifically targeted for harassment and arrest.

The ADF is deliberately structured as an ISIS franchise. The organization studies ISIS methodology, adopts its propaganda framing, and extends its theological justification to the Central African context. It represents not an isolated insurgency but a nodes in a transnational jihadist network operating under shared ideological instruction.

IRAQ AND SYRIA: THE YAZIDI PRECEDENT

The Yazidi genocide of August 2014 set a precedent for what industrial-scale religious persecution looks like when ISIS controls territory. On August 3, 2014, ISIS launched a coordinated offensive against Sinjar City and surrounding towns in Iraq’s Nineveh Governorate, the homeland of the Yazidi religious minority. What followed was methodical genocide.

Tens of thousands of Yazidis fled toward Mount Sinjar seeking refuge. ISIS encircled the mountain on August 4, trapping an estimated 2,000-7,000 people on barren peaks in temperatures exceeding 50 degrees Celsius, without water, food, or shelter. On that mountain, Yazidis died from dehydration, malnutrition, and suicide. Children suffocated in crowded spaces as families fled. Academic estimates conducted by researchers at the University of Illinois placed the death toll at approximately 3,100 Yazidis killed and 6,000 or more kidnapped for sexual slavery and forced labor—9,900 people total affected in the span of days.

The mechanics of the genocide were documented with precision by the U.N. Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights and the U.N. Assistance Mission for Iraq. Male Yazidis were separated from females and children. Men were executed, often beheaded or shot. Women and girls were abducted into a systematic sex slavery apparatus, transported across ISIS-held territory, and sold or given to ISIS fighters as property. Boys were conscripted into ISIS military training programs. The genocide was not random violence—it was orchestrated policy designed to erase a religious minority.

The Christian experience in Iraq’s Nineveh Plain paralleled the Yazidi catastrophe. In June 2014, ISIS took control of Mosul, forcing approximately 500,000 people to flee. Among them were tens of thousands of Christians who had inhabited the city and surrounding villages for nearly two millennia. When ISIS captured all Assyrian towns in the Nineveh Plain in August 2014, Christians were given an ultimatum: convert, pay a special tax, leave, or be executed. ISIS marked Christian homes with the Arabic letter “N,” for Nasrani (Christian), which became a global symbol of solidarity with persecuted Christians. The letter was not a designation of protection—it was a death warrant.

The Christian population of Iraq has collapsed from approximately 1.5 million in 2003 to roughly 200,000 today. Most fled. Some were killed. All were marked as targets. Even after ISIS’s territorial defeat in 2017, Christians have hesitated to return, citing renewed sectarian tensions and the absence of state protection in Nineveh.

The Yazidi and Christian cases are instructive because they show what happens when jihadist ideology gains territorial control and legal authority. The violence is not spontaneous—it is bureaucratic. ISIS issued written directives on treatment of non-Muslims, established hierarchies of persecution, and executed policy consistently across its controlled territory. It represents the operational expression of the theological framework extremists derive from selected Islamic texts.

PAKISTAN: THE BLASPHEMY LAW APPARATUS

In Pakistan, persecution operates through a different mechanism: state law weaponized as an instrument of religious violence. The nation’s blasphemy laws—codified in its Penal Code as Sections 295-298—carry sentences ranging from ten years imprisonment to death for desecrating the Quran, insulting Islam, or insulting Prophet Muhammad.

Between 1987 and 2023, at least 2,449 people were accused of blasphemy under these laws. Of those accused, approximately 25% were Christians—despite Christians comprising just 1.8% of Pakistan’s 240 million population. The disproportionate targeting is not coincidental. Christians are easier to accuse in a majority-Muslim society where mere rumor or personal vendetta can trigger mob mobilization.

In 2023 alone, 329 blasphemy accusations were filed—nearly one per day. Of these, 11 were against Christians. But the statistics mask the mechanism: once accused, a Christian faces not just legal jeopardy but extrajudicial violence. Between 1994 and 2023, at least 95 people were killed in mob violence related to blasphemy accusations, according to the Centre for Social Justice. In June 2024, a 73-year-old Pakistani Christian named Lazar was beaten to death by a mob after being falsely accused of burning the Quran.

The cases cluster in Punjab, Sindh, and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa provinces, where organized networks of religious activists and clerics mobilize mobs upon hearing accusations. The mechanism is simple: a personal dispute escalates into a blasphemy allegation; the allegation spreads through mosques and social media; a mob forms; police either participate or refuse to intervene; Christian individuals are murdered; courts prove slow to convict perpetrators.

In some cases, false accusers face no consequences. The system is designed to function as extrajudicial punishment wrapped in legal language. USCIRF has documented that over 450 people have faced false blasphemy accusations in recent periods, suggesting organized targeting rather than organic outrage.

Forced conversions represent a secondary persecution mechanism in Pakistan. Christian girls and women are abducted, raped, and coerced into Islamic marriage ceremonies, with their conversion used to obscure kidnapping and sexual assault. The legal system offers minimal protection—girls are deemed to have “converted” and are therefore no longer considered Christian victims, even when evidence of coercion is present.

Pakistan’s blasphemy apparatus demonstrates that religious persecution does not require jihadist militias. State law, selectively enforced and amplified by organized religious movements, can achieve comparable destruction.

KENYA AND EAST AFRICA: AL-SHABAAB’S SECTARIAN TARGETING

On April 2, 2015, gunmen stormed Garissa University College in northeastern Kenya. The attack began at 5:30 a.m. when masked, armed attackers killed two unarmed guards at the entrance. They then proceeded systematically through dormitory buildings, separating students by religion. Those identified as Christian were executed on the spot. The attackers held approximately 700 students hostage for hours while methodically executing Christians. By the time Kenyan security forces killed all four attackers, 148 people were confirmed dead—mostly university students.

The perpetrator was Al-Shabaab, an al-Qaeda-aligned jihadist organization based in Somalia. In a statement to journalists and on its website, the group explicitly framed the attack as retaliation: “When our men arrived, they released the Muslims but were holding Christians hostage,” according to spokesman Sheikh Ali Mohamud Rage. The group declared that Kenyan intervention in Somalia constituted a “crusader invasion” and promised that “Kenyan cities will run red with blood” until Muslim lands were “liberated.”

Al-Shabaab has conducted repeated attacks on Christian communities across Kenya and Tanzania, using the same theological framework as ISIS, Boko Haram, and other jihadist organizations: Kenya’s intervention in Somalia is portrayed as a Christian crusade; therefore, killing Kenyan Christians constitutes legitimate jihad. The group has conducted suicide bombings in shopping malls, coordinated attacks on Christian villages, and maintained an ideological commitment to establishing Islamic governance across the Horn of Africa.

THE MEDIA APPARATUS: STRATEGIC OMISSION AND LANGUAGE LAUNDERING

The violence targeting Christians in Nigeria meets every definitional threshold for religious persecution, yet mainstream international media consistently frames it through alternative lenses, neutering the religious motivation in favor of narratives emphasizing resource competition, banditry, or state failure.

Consider the mechanics of omission. On Palm Sunday 2025, April 13, Islamic extremists murdered 54 Christians in coordinated attacks. France’s leading newspaper, Le Monde, published coverage of the attack but deliberately omitted that it occurred on Palm Sunday—a fact that would establish clear religious targeting. Similarly, Christmas 2023 and 2024 massacres of Christians were reported by CNN and Deutsche Welle without mentioning Christmas or identifying the victims’ religious identity. A June 2022 massacre inside a Catholic church in Nigeria killed 40 Christians inside a place of worship; NPR covered the incident but buried the religious dimension, framing it instead through the lens of pastoral land disputes.

This is not random editorial choice. A cascade of 2025 BBC investigations and articles by mainstream outlets adopted coordinated skepticism toward Christian persecution narratives, despite documented evidence from on-the-ground monitors. The BBC’s “Global Disinformation Unit” published an article headlined “Are Christians Being Persecuted in Nigeria as Trump Claims?” that treated the question as settled by citing denials from the Nigerian government itself—the state entity most directly responsible for failure to protect persecuted minorities.

When contacted by BBC journalists, the Nigerian-based human rights organization Intersociety (which compiles casualty data from on-the-ground monitors and eyewitness accounts) was unable to provide itemized receipts for each recorded death—an impossible standard given that violence occurs in conflict zones with limited access and no functioning census system. Rather than acknowledging the evidentiary constraints inherent to documenting violence in ungoverned territories, the BBC concluded the figures were “difficult to verify” and therefore suspect. CNN cited the Nigerian government’s statement that “terrorists attack all who reject their murderous ideology—Muslims, Christians and those of no faith alike,” presenting this official denial as evidence against religious targeting, despite the fact that jihadist targeting of Christians is qualitatively different from killing of insufficiently radical Muslims.

The strategic obfuscation operates on multiple levels. When reporting on Nigeria’s violence, outlets employ a consistency of framing: frame the violence as “multifaceted,” cite the existence of Muslim victims (true but contextually misleading), and then argue that religious motivation cannot be “justified” because some victims span multiple faiths. This inverts logical causality. The existence of Muslim victims does not negate targeting of Christians; it demonstrates the complexity of jihadist targeting. ISIS executed both moderate Muslims and Christians. Al-Qaeda killed both Shia Muslims deemed apostates and Christians. Boko Haram targets both “insufficiently Islamic” Muslims and Christians. This multipolar targeting is a feature of jihadist operations, not evidence that religious motivation is absent.

Tony Perkins, former chair of the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom, stated publicly: “Many Western news outlets, taking their cues from the previous administration, continue to overlook the accelerating violence and bloodshed currently taking place in Africa, which is perpetrated mainly by radical Islamist groups.” The statement suggests editorial direction from political actors—a systematic de-prioritization of Christian persecution coverage under the Biden administration, followed by sudden amplification under Trump. This is not investigative journalism; it is narration shaped by political cycles.

The cumulative effect is that 4,476 Christians killed globally for their faith in 2024 alone received a fraction of the international media attention devoted to single incidents in geopolitically central regions. Meanwhile, 16.2 million Christians forcibly displaced in sub-Saharan Africa languish in IDP camps receiving inadequate humanitarian assistance—a displacement crisis dwarfing many conflicts that receive sustained coverage.

HUMAN RIGHTS NGOS: THE SELECTIVE ADVOCACY PROBLEM

The universe of international human rights organizations includes bodies with mandates explicitly encompassing religious freedom. Yet structural biases within NGO ecosystems have systematically deprioritized Christian persecution, particularly in Muslim-majority contexts.

Amnesty International, the world’s largest human rights NGO by membership and budget (approximately £293 million annually), has faced documented criticism for treating persecuted Christians in Muslim-majority contexts as an afterthought. A 2025 analysis of Amnesty’s reporting noted that the organization has “virtually forgotten” Christian persecution, while Christianity is frequently referenced by Amnesty as part of the far-right movement in the United States. In its 2025 report on the State of the World’s Human Rights, Amnesty did document escalating Christian persecution in specific regions (Sudan, Iran, China, Nicaragua, Cuba), but the emphasis and resource allocation remains disproportionate to the scale of persecution.

The asymmetry is not random. Amnesty’s leadership and donor base skew toward progressive constituencies skeptical of religious framing broadly and of Christian advocacy specifically—constituencies viewing Christian persecution narratives as potentially weaponizable by conservative political actors. This creates institutional incentives to treat Christian persecution as lower priority than, for example, LGBTQ+ rights violations or gender-based violence, even when persecution reaches genocidal scale.

Human Rights Watch (HRW), another major international NGO, published a report titled “DR Congo: Armed Group Massacres Dozens in Church” documenting the Komanda massacre in which 40+ Christians were beheaded inside a Catholic church compound. HRW’s reporting was factually accurate. Yet the organization’s broader Nigeria coverage has employed language designed to neutralize religious targeting—framing violence as “communal conflict” or “intersectional” without centering the explicit jihadist targeting of Christians.

The most consequential NGO in the Christian persecution space—Open Doors—operates with greater rigor and transparency than mainline human rights organizations. Open Doors maintains the World Watch List, a 30-year-standing dataset tracking persecution across 78+ nations. The 2025 World Watch List documented that 380 million Christians face persecution, with 78 countries crossing the high-persecution threshold. Yet Open Doors’ reports, while exhaustive, receive a fraction of the international attention accorded to Amnesty or Human Rights Watch reports on other issues. The gap reflects both NGO size differential and media prioritization biases.

Aid to the Church in Need (ACN), a Catholic-affiliated organization, produced the 2025 “Religious Freedom in the World Report” identifying 62 countries with grave religious freedom violations affecting 5.4 billion people, with 24 classified as “persecution” and 36 as “discrimination.” Yet ACN’s reach remains limited, with the report receiving minimal coverage in mainline media outlets. The disparity between ACN’s documentation and international media amplification suggests that accurate religious persecution data, when produced by faith-affiliated organizations, faces institutional skepticism from secular media gatekeepers.

THE UNITED NATIONS AND INTERNATIONAL BODIES: STRUCTURAL INADEQUACY

The United Nations, with its mandate to uphold the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and Article 18’s guarantee of religious freedom, has demonstrably failed to mobilize enforcement mechanisms against systematic Christian persecution.

The UN Human Rights Council employs Special Rapporteurs tasked with monitoring violations in specific domains. The Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief holds the mandate to investigate religious persecution globally. Yet the position has historically lacked enforcement authority, adequate staffing, and political support from Security Council permanent members, several of which (notably China and Russia) have themselves engaged in Christian persecution or harbored allies who do.

International Christian Concern documented in April 2025 that “the UN isn’t doing enough” to protect persecuted Christians, noting that nations including Eritrea, Pakistan, and Vietnam “relentlessly persecute Christians and are free from sanctions” despite the UN’s stated capacity to impose sanctions, sever diplomatic relations, or authorize military force. The report identifies an asymmetry: while nations violating other human rights standards face Security Council scrutiny and potential sanctions, religious persecution—even at genocidal scale—rarely triggers comparable enforcement response.

The International Court of Justice (ICJ), the UN’s principal judicial body, has been asked to adjudicate genocide allegations in specific contexts (notably Myanmar against Rohingya Muslims) but has not mobilized comparable urgency toward Christian persecution cases in Nigeria, DRC, or parts of the Middle East.

Explanations for this institutional inertia are multiple: religious persecution cases implicate powerful state actors (Iran, Russia, China) or strategic allies (Saudi Arabia’s involvement with Sunni militias in Yemen and Syria); permanent Security Council members with veto power block action; and religious persecution is often conflated with political instability rather than treated as an independent human rights violation deserving enforcement.

The result is that Christians killed in Nigeria remain statistically undercounted in UN databases, IDPs living in camps without adequate aid receive no Security Council-mandated humanitarian intervention, and perpetrators operate without fear of international prosecution.

NATIONAL GOVERNMENTS: POLITICAL CALCULATION AND COMPLICITY

Several national governments have either actively enabled Christian persecution or deliberately minimized it for geopolitical reasons.

The Biden administration (2021-2025) removed Nigeria from the State Department’s “Countries of Particular Concern” list in 2021, despite Boko Haram and ISWAP continuing active operations that killed thousands of Christians annually. The removal occurred amid broader diplomatic engagement aimed at positioning Nigeria as a strategic partner in West African counterterrorism operations. The administration prioritized military partnership over religious freedom advocacy, a calculation reversed under the Trump administration, which redesignated Nigeria as a Country of Particular Concern in November 2025.

Pakistan’s government, despite international scrutiny, continues to enforce blasphemy laws that serve as instruments of religious persecution. The criminal code provisions (Sections 295-298) that penalize insulting the Prophet or religion have never been repealed despite decades of advocacy from human rights organizations and international bodies. Pakistan’s government maintains these laws partly for domestic political reasons (appeasing religious conservative constituencies) and partly due to strategic alignment with Saudi Arabia and Gulf states that promote conservative Islamic jurisprudence.

The Nigerian government under President Bola Tinubu explicitly denies that Christian persecution occurs at systematic scale, framing violence as “indiscriminate” and “rooted in competition over resources.” This denialism enables the government to avoid implementing targeted protections for Christian communities, continue neglecting Christian-majority regions in security force deployment, and avoid prosecuting Fulani militia members and Boko Haram leaders who operate with apparent impunity.

DATA WARFARE: THE INTERSOCIETY CONTROVERSY

Beginning in November 2025, a controversy erupted regarding the reliability of casualty figures cited in Christian persecution advocacy. The International Society for Civil Liberties and Rule of Law (Intersociety), a Nigerian NGO founded in 2008 by Emeka Umeagbalasi, compiles statistics on violence in Nigeria through a combination of primary sources (direct observation, eyewitness accounts) and secondary sources (researcher accounts, third-party reports). Intersociety’s figures—125,000 Christian deaths since 2009, 19,100 churches destroyed, 7,000 deaths in the first 220 days of 2025—became central to international advocacy and influenced U.S. policy (Trump’s redesignation of Nigeria as Country of Particular Concern).

In November 2025, the BBC Global Disinformation Unit published an investigation suggesting that Intersociety’s methodology lacks transparency and relies on “unverified summary statistics” rendering independent confirmation “impossible.” The BBC noted that when it analyzed sources cited by Intersociety for specific 2025 death tallies, roughly half of the incidents cited did not specify the victims’ religion, raising questions about attribution methodology.

Intersociety responded by publishing a statement defending its methodology, noting that tracking violence in regions where jihadist groups maintain territorial control and where government recordkeeping is nonexistent creates inherent verification challenges. The organization argued that the BBC’s standard—requiring itemized proof for each of 7,000 deaths—is impossible to meet in conflict zones and represents a standard not applied to other casualty estimates in similarly chaotic environments.

The BBC investigation also noted that Intersociety and related advocacy groups have connections to Igbo nationalist and separatist sentiment in southeastern Nigeria, raising the question of whether casualty reporting is inflated to serve ethnic and political grievances alongside religious freedom concerns. The BBC noted that while Intersociety presents itself as an NGO focused on religious persecution, its founding leader Umeagbalasi has close ties to supporters of the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB), a separatist organization seeking secession from Nigeria.

This controversy is not merely academic. If Intersociety’s figures are significantly inflated—whether through methodological error or deliberate exaggeration—the entire advocacy framework for Christian persecution collapses. Conversely, if the BBC investigation itself is shaped by institutional bias against religious persecution narratives or by deference to Nigerian government denials, then the “fact-checking” itself constitutes complicity in minimizing genocide.

The most rigorous independent source, the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED)—a U.S.-based nonpartisan research group cited by major news organizations—documents approximately 52,915 civilians killed in Nigeria through “targeted political violence” since 2009, with both Christian and Muslim victims. Of these deaths, ACLED’s attribution of deaths “specifically targeting Christians” versus deaths in broader conflict varies, but even conservative ACLED estimates document at least 3,000 Christian deaths in 2025 alone. This remains a rate vastly exceeding documented Christian deaths in any other single nation.

The evidentiary dispute cannot be resolved by reference to perfect data. The fact is that reliable independent verification of individual casualty figures in active conflict zones is inherently impossible. Governments do not maintain accurate records. Jihadist groups do not publish casualty manifests. Families do not report every killing to human rights monitors. The question therefore becomes: given inherent fog of war, should the international community operate on the assumption that figures are inflated, or should it operate on the assumption that figures are systematically undercounted?

Open Doors’ 30-year track record suggests systematic undercounting. The organization has documented escalating persecution across three decades without apparent political bias or ethnic affiliation. Open Doors documented 380 million Christians facing persecution in 2025—a 15 million increase in one year. If undercounting were not operative, year-over-year increases of this magnitude would indicate a sudden velocity to persecution absent prior trajectory. The more plausible inference is that persecution has been undercounted for decades and international attention is only now catching up to documented reality.

THEOLOGICAL MISDIRECTION: MISREPRESENTING ISLAM TO PROTECT INSTITUTIONS

A secondary form of institutional complicity operates at the theological level. When Christian persecution by jihadist groups is acknowledged, it is frequently reframed as “distortion” of Islam perpetrated by fringe extremists, with the implicit message that Islam itself is peaceful and that targeting Christian persecution is inherently anti-Islamic.

This framing is not entirely wrong—it is partly true that mainstream Islamic scholarship rejects jihadist theology. But the strategic emphasis serves institutional interests. International development organizations, bilateral aid agencies, and secular human rights NGOs have adopted de facto policies of defending Islam against charges that certain Islamic ideologies produce violence targeting Christians and other minorities. This defensiveness reflects legitimate concern about Islamophobia and religious bigotry; it also reflects structural bias against centering Christian persecution narratives in secular institutional spaces.

When Open Doors or Aid to the Church in Need documents Christian persecution by “Islamic extremists,” secular NGOs and media outlets respond by emphasizing that “Islam is a religion of peace” and that most Muslims reject extremism. This response, while factually correct regarding mainstream Islam, deflects from the central fact: jihadist organizations explicitly use Islamic texts to justify targeting Christians, and this theological framework is operational—it mobilizes recruiters, justifies violence to combatants, and remains internally consistent within its interpretive logic.

Avoiding discussion of how jihadist organizations weaponize Islamic texts and theological concepts (takfir, jizya, abrogation of peace verses) does not protect Islam or promote interfaith dialogue. It obscures the mechanics through which violence is justified and fails to create space for the theological pushback that Muslim scholars themselves conduct against extremist distortion.

DISPLACEMENT AID DISCRIMINATION

A final form of institutional complicity operates through aid discrimination in displacement camps. Open Doors documented in a 2025 advocacy report that in Nigeria’s Borno State, Christian internally displaced persons report “systemic exclusion from government-run aid programmes.” The finding parallels documentation from Yemen showing that Christian IDPs face “discrimination in aid distribution” alongside violence from extremists.

Aid distribution systems, whether operated by UN agencies (UNHCR, WFP), international NGOs (ICRC, World Vision), or national governments, frequently operate on the assumption that religious minorities are small populations requiring marginal resource allocation. When persecution displaces predominantly Christian communities, the aid apparatus systematically underserves them. In camps housing both Muslim and Christian IDPs, Christian populations are often fewer and therefore prioritized for lower resource allocation per capita despite facing identical risks.

This discrimination is not always deliberate. It reflects systemic biases in humanitarian aid delivery: operational difficulty in identifying religious identity amid displacement; prioritization toward majority religious groups (simpler logistics); and international NGO reluctance to highlight religious dimensions of persecution (due to the political risks outlined above).

The consequence is measurable: 16.2 million Christians forcibly displaced in sub-Saharan Africa languish in camps in what Open Doors describes as “unbearable conditions,” with documented inadequacy in water access, food distribution, medical care, and security. This represents a humanitarian crisis of magnitude comparable to Syria or Afghanistan, yet receives a fraction of international attention, funding, and advocacy.

THE SCRIPTURAL ARCHITECTURE OF JIHAD

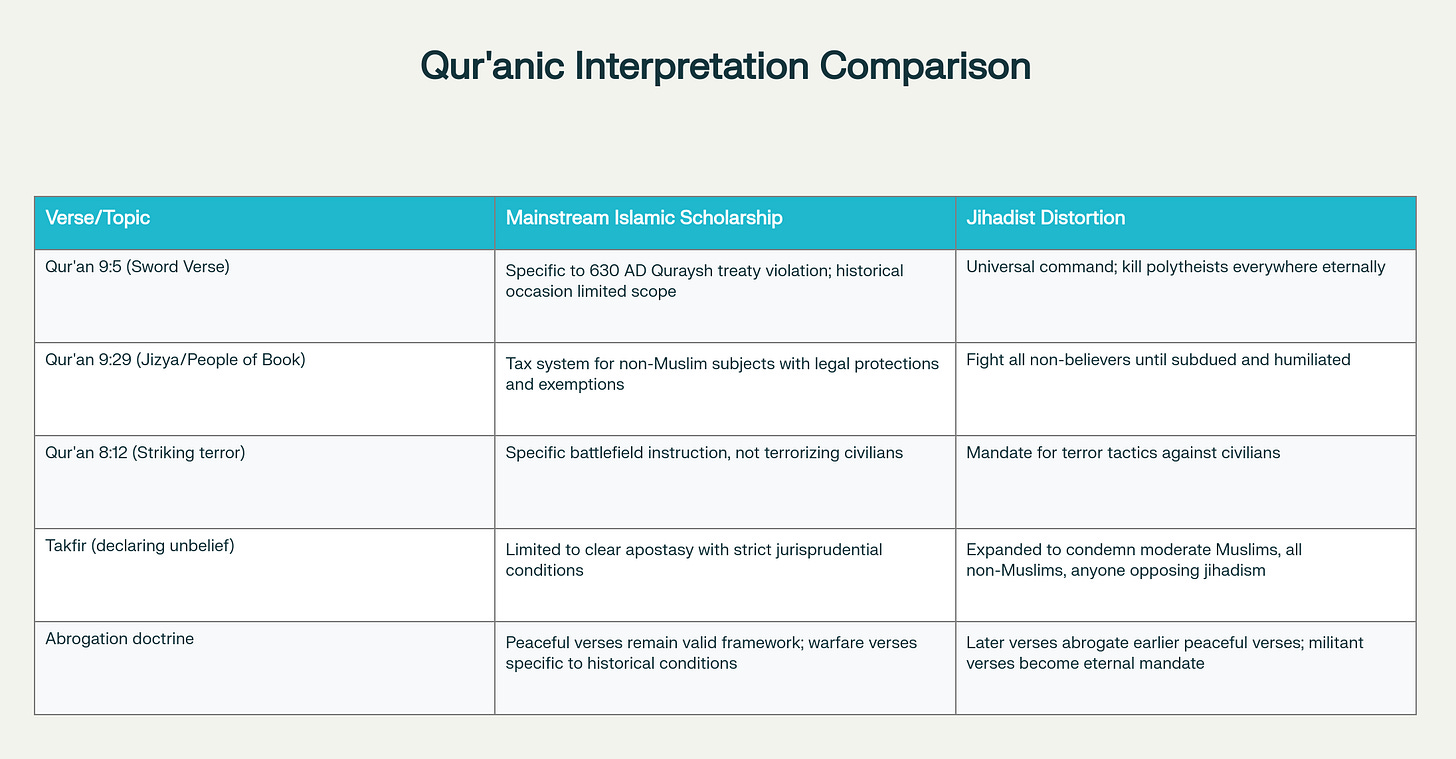

All of these organizations—ISIS, Boko Haram, ISWAP, ADF, Al-Shabaab, and the networks supporting blasphemy violence in Pakistan—justify their actions through selective citation of Islamic theology. The pattern is consistent. A small cluster of Qur’anic verses is extracted, de-contextualized, and presented as eternal mandates for warfare against non-Muslims and against Muslims deemed insufficiently zealous.

The verses they repeatedly invoke:

Qur’an 9:5, “The Verse of the Sword.” The full verse reads: “But once the Sacred Months have passed, kill the polytheists wherever you find them, capture them, besiege them, and lie in wait for them on every way. But if they repent, perform prayers, and pay alms-tax, then set them free. Indeed, Allah is All-Forgiving, Most Merciful.”

Extremists cite only the killing clause and strip away the conditional forgiveness and the historical context. According to Islamic exegesis (tafsir) by classical scholars including al-Baydawi and al-Alusi, verse 9:5 refers specifically to pagan Arabs (the Quraysh) who violated their peace treaties with the Prophet Muhammad in 630 AD. The verse is introduced by verses 9:1-4, which specify that the revelation concerns polytheists who had broken treaties and violated protections for Muslims. Verse 9:6 immediately follows, offering protection to those polytheists who ask for it and wish to hear the Qur’an. The verse, in context, addresses a specific historical situation, not a general mandate for perpetual warfare against all non-Muslims.

Jihadist theologians, particularly those schooled in Salafi-jihadist doctrine, apply a doctrine called “abrogation” to argue that these warfare verses supersede and cancel out verses emphasizing peace, protection of non-Muslims, and limitations on violence. One academic paper analyzing ISIS theology documents the group’s systematic misuse of abrogation: “Recently, salafi-jihadists have applied the doctrine of abrogation in a more intense way, abrogating the verses that for centuries tempered the concepts of takfir and jihad and laying increased emphasis on later revelations.” This is not a mainstream Islamic position. Mainstream Islamic jurisprudence does not accept that warfare verses universally abrogate peace verses; rather, both sets of verses are understood to apply to their specific contexts.

Qur’an 9:29, “The Jizya Verse.” This verse states: “Fight those who do not believe in Allah or in the Last Day and who do not consider unlawful what Allah and His Messenger have made unlawful and who do not adopt the religion of truth from those who were given the Scripture—fight until they give the jizyah willingly while they are humbled.”

The jizyah (also spelled jizya) is a tax paid by non-Muslim subjects (dhimmis) living under Islamic governance. In classical Islamic jurisprudence, the jizya is part of a system granting non-Muslims protection, legal standing, and exemptions from military service. Christians and Jews were understood to have protected status as “People of the Book” who shared an Abrahamic tradition. The verse is specific to the conditions under which a jizyah could be imposed.

Jihadists universalize this verse to argue that Islam mandates fighting all non-Muslims “until they pay the jizya and feel subdued”—applying a historical tax system to a timeless warfare mandate. They ignore the verse immediately preceding it (9:28), which discusses the polytheists of Arabia being prevented from approaching the Sacred Mosque, and the broader Qur’anic framework offering legal protection to non-Muslim minorities.

Qur’an 8:12, “The Terror Verse.” This verse states: “I will cast terror into the hearts of those who have disbelieved, so strike [at] their heads and strike from them every fingertip.”

ISIS, Boko Haram, and other jihadist organizations cite this as authorization for terror attacks and beheadings. The verse appears in Surah al-Anfal (Chapter 8), which addresses battlefield conduct during the Battle of Badr in 625 AD, a specific engagement between the Prophet’s forces and Meccan pagan armies. The verse refers to battlefield psychology—the terror experienced by combatants facing Muslim warriors—not a mandate for terrorizing civilians. In context, the next verse and subsequent passages discuss treatment of prisoners, ransom, and rules of engagement specific to historical warfare.

Qur’an 47:4, “The Striking Verse.” This verse states: “So when you meet those who disbelieve, strike [at] their necks until, when you have inflicted slaughter upon them, then secure the bonds, and either [confer] favor afterwards or ransom [them] until the war lays down its burdens.”

ISIS and similar organizations cite this verse to justify beheadings of prisoners, exactly as documented in DRC church massacres. The verse appears in Surah Muhammad (Chapter 47) and, in context, addresses procedures for warfare and treatment of prisoners of war. The verse discusses ransoming prisoners—implying their survival—and immediately follows verses about discipline of fighters. It does not authorize execution of civilians.

Takfir Doctrine. All jihadist organizations employ what Islamic jurisprudence calls “takfir”—the declaration that a person has left Islam and is therefore an apostate. Classical Islamic law restricted takfir to explicit rejection of the faith with public proclamation. Jihadist doctrine radically expands takfir to include: Muslims who do not support jihad, Muslims who work with secular governments, Muslims who reject the caliphate, Christians, Jews, Hindus, Yazidis, and any person opposing the group’s agenda.

An academic paper analyzing ISIS’s use of takfir states: “ISIS had this very ‘blessing’ in mind when, in the third issue of Dabiq, they called Muslims everywhere to join them... In verse 38, Allah gives a sharp rebuke to non-violent Muslims... This verse says that those who jihad (fight) the pagans in war, risking their lives and forsaking...” The organization weaponizes Qur’anic rebukes to those who refuse to fight and treats refusal to support the jihadist cause as apostasy warranting execution.

This is systematic distortion. It is not isolated misreadings by marginal clerics—it is coordinated theological methodology taught in ISIS training camps, articulated in Boko Haram ideological statements, and deployed by ADF recruitment propaganda.

Chart showing the comparative interpretation of key verses now embedded.

THE MAINSTREAM ISLAMIC PUSHBACK

It is crucial to note: mainstream Islamic scholarship rejects this interpretive framework categorically.

Muslim clerics, theologians, and organizations have issued formal rebuttals to jihadist theology. The Association of Muslim Scholars in Iraq and other mainstream religious bodies have condemned ISIS and issued detailed theological critiques of the organization’s scriptural methodology. Scholars including Dr. Yasir Qadhi have publicly explained that the “Sword Verse” (9:5), when placed in historical context and read with surrounding verses, does not authorize universal warfare but rather addresses a specific historical moment: the violation of a peace treaty by the Quraysh in 630 AD.

Mainstream tafsir (exegesis) by Ibn Kathir, al-Baydawi, al-Alusi, and other classical authorities explicitly contextualize warfare verses to specific historical situations. The peace verses of the Qur’an—emphasizing “there is no compulsion in religion” (Qur’an 2:256) and advocating for peaceful coexistence with non-Muslims—are understood not to be abrogated but to form the broader legal framework.

Academic research on ISIS’s theology demonstrates that the organization “cherry-picks and de-contextualizes” scripture, applying verses to situations entirely different from their historical revelation. One study notes that “with sedition widely condemned by established scholarship and only 0.4% of the Qur’an concerned with warfare, the expediency of such reasoning for the Islamic State is clear.”

The point is not that Islam contains no verses permitting warfare—it does, as do the Hebrew Bible and Christian New Testament under specific conditions. The point is that extremists weaponize warfare texts while ignoring the jurisprudential constraints, historical contexts, and peace-oriented verses that mainstream Islamic scholarship uses to balance their application.

INTERNATIONAL INACTION AND THE DISPLACEMENT CRISIS

Despite this documentation, the international response has been inconsistent and inadequate. In sub-Saharan Africa, 16.2 million Christians have been forcibly displaced, living in Internally Displaced Persons camps in what Open Doors describes as “unbearable conditions.” Many camp residents lack access to employment, have lost land and homes, and face discrimination in humanitarian aid distribution, with religious minorities receiving fewer resources than Muslim IDPs.

The displacement extends beyond Africa. Christians fleeing Iraq and Syria number in the hundreds of thousands, with many permanently resettled in diaspora, draining Middle Eastern Christian communities of centuries of continuity.

One factor explaining international hesitation is the complexity of conflicts. In Nigeria, the violence cannot be reduced to simple “Christian persecution.” The Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project notes that most victims of Boko Haram and ISWAP are actually Muslims, including those deemed apostates or collaborators. The farmer-herder conflicts are rooted in climate change, desertification, and competition for resources, not purely religious animus. Some analysts argue that framing Nigeria’s violence as religious persecution risks oversimplifying geopolitical realities and fueling religious polarization.

These analysts are not entirely wrong. The violence is multi-causal: religious extremism, resource scarcity, weak state capacity, proliferation of weapons, and political failure all contribute. But the error lies in treating religious targeting as incidental to these factors. Religious extremism is not a symptom of resource conflict—it is an organizing principle. Jihadist ideology provides the framework for mobilization, recruitment, and tactical coordination. Removing the religious dimension from analysis would be equivalent to analyzing Nazi genocide while ignoring antisemitism because Jews were targeted alongside other groups deemed racially inferior.

The question of Trump’s November 2025 military intervention threat is illustrative. Trump correctly identified that Christians face systematic targeting but misunderstood the nature of the problem. Military intervention cannot address the underlying theological distortion or the state failure enabling armed groups. Additionally, unilateral U.S. military operations in Nigeria would likely exacerbate instability and prove counterproductive.

A comprehensive response requires: enhanced protection for Christian communities, international support for strengthening Nigerian state capacity, documentation of atrocities for potential prosecutions, support for internally displaced persons with humanitarian assistance, theological engagement with mainstream Muslim leaders to isolate extremist interpretations, and international pressure on neighboring states and transnational jihadist networks enabling the violence.

MOMENTUM TOWARD GENOCIDE

The trajectory is clear. Christian persecution is not a static condition but an accelerating one. The 380 million Christians now facing persecution represent a 15 million-person increase in just one year. Seventy-eight countries now meet the persecution threshold, compared to the 50 that formed the original World Watch List. In Nigeria, the stated goal of some jihadist organizations is the elimination of 112 million Christians within 50 years.

In the DRC, the ADF is operating with impunity, conducting massacres at churches with minimal international intervention. In Pakistan, the blasphemy apparatus continues to function as an instrument of religious murder, with courts proving reluctant to convict perpetrators despite overwhelming evidence.

The theological framework driving this violence is not spontaneous—it is taught, refined, and disseminated through structured networks. ISIS training camps produce ideologues who export the framework to regional franchises like ISWAP and ADF. Boko Haram ideological statements directly parallel ISIS theology. Al-Shabaab propagandists employ identical scriptural distortions. This is not coincidental coordination—it reflects a transnational jihadist intellectual apparatus functioning with remarkable consistency despite geographical dispersion.

The primary responsibility for stopping this violence rests with affected states and regional security forces. Nigeria must increase military capacity, reduce corruption in security apparatus, and remove political actors who enable jihadist groups. The DRC must strengthen governance and protect civilians in the east. Pakistan must reform or repeal blasphemy laws and prosecute perpetrators of mob violence. Kenya and East African states must coordinate against Al-Shabaab and cut funding sources.

But international actors have a responsibility to provide support, documentation, and pressure. The Open Doors World Watch List has established baseline data that can inform policy and resource allocation. USCIRF reports have identified specific governmental actors and networks enabling persecution. International criminal courts have jurisdiction to prosecute crimes against humanity in Syria and Iraq. The United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights has documented war crimes.

What is absent is political will to treat this as a crisis demanding coordinated response. Instead, the violence persists in international media as a steady drumbeat of isolated atrocities: another church bombed in Nigeria, another massacre in the DRC, another blasphemy conviction in Pakistan. The isolation obscures the pattern. The pattern reveals an organized architecture of religious genocide operating across multiple continents, employing shared theological distortions, and targeting a population of 380 million people—one in seven Christians on earth.

The question is not whether the persecution is real. The data is overwhelming and verified by multiple independent organizations. The question is whether the international community will treat it as the systematic, coordinated genocide it has become.